In this article, we'll start with the premise that you are writing (or starting) a series of novels set in the same universe. Here not only will you discover how to manage the books from your series in a single project file, but you'll also learn how to make the most of the keywords feature in Scrivener by setting up keywords in a structured fashion.

Wollen Sie diesen Artikel auf Deutsch lesen wollen? Gehe hier hin.

Don't forget that this blog is now for behind-the-scenes reporting on the Armada Wars universe, and RCV's posts on writing and for writers. All of the current news and events going on in the Armadaverse can now be found on the all new web site at www.ArmadaWars.com!

One of the most powerful features of Scrivener — or rather 'aspects' of Scrivener, since it's not a single feature — is the information management capability. For most people, the management of their project will rely on meta-data and keywords.

A Word About Meta-Data

This article is mostly to do with Scrivener's keywords, but meta-data also bears mentioning.

Scrivener allows you to add custom meta-data to scenes. This means you can have your own arbitrarily defined meta-data attached to each scene, which provides you with several ways of not only categorising those scenes, but finding and manipulating them.

The meta-data fields you set up might be anything: towns or planets where action takes place, time periods if your story involves an element of time travel, differentiation between normal scenes, dreams, and flashbacks, and so on.

You can define meta-data fields by going to Project->Meta-Data Settings (Alt+Cmd+comma on a Mac).

Populating meta-data is easy: you can do it as you write or create scenes. Once the data is in there, visibility of those values can be switched on or off in the Outliner view (this is the pane in Scrivener which lets you see a list of folders, documents and sub-documents in whichever folder you have selected in the project's Binder.)

You can then order the scenes and other documents by your meta-data, grouping them by location, scene type etc. You can even change meta-data directly from this view. Meta-data fields are searchable in Scrivener's search box, so you can also make collections of scenes with specific field values — for example, a collection of all scenes which take place on Earth.

Using a Single Project for a Series

If like me you have a number of books which all belong to the same story, or if you plan a series which revolves around the same people and events, you might want to consider using a single Scrivener project.

This method is suited to any series with a main story which is all the same over-arching narrative, a story in which most of the characters and locations are revisited, or a story in which events in earlier books have consequences in later books.

Well-known examples of such series would be:

- The Harry Potter series,

- Divergent series,

- Maze Runner,

- The Hunger Games.

|

| Image 1 |

As you can see, the compile group is set to The Ravening Deep, which is the book I am currently writing.

All of the other books in the GWOTS story are in their own folders outside of the compile group. This means that my writing targets are only based on the current and required word counts for The Ravening Deep.

You might notice the books outside the compile group have brown book icons instead of Scrivener's default blue folders: I just changed the icons to make those books easier to find. Right-click on any item's icon to change it.

(Those two books near the bottom have their names scrubbed out because they have not yet been announced).

Although four of the books are outside the compile group, they can still use all the same meta-data and keywords that are used in The Ravening Deep, because they are all contained in the same project.

Creating Keywords

|

| Image 2 |

The advantage of starting out this way is that you will not end up with a vast list of keywords which you have to navigate alphabetically every time you want to tag a keyword onto a scene.

Image 2 shows the keyword parents which I have set up for the GWOTS story.

You'll notice that they are broad categories which pretty much cover every area or topic which might contain a reference I'll want to tag scenes with.

Some categories are quite narrow, such as "Characters". That one speaks for itself: all of the actual character keywords will be children of that category.

If necessary, sub-categories can be added for "main characters", "secondary characters", "throwaway characters", and so on.

Other categories are quite broad. The one I have called "references" is a good example: this one is for keywords which relate to the oft-repeated, culturally idiomatic expressions found in the Armada Wars books, for example the honorific phrase "Ottomas Endures".

Let's take a look at the keywords in a couple of categories.

Defining Keywords

|

| Image 3 |

You might wonder why I don't just have a "locations" category. The simple answer is that the planets need their own tags, because there is a map of the Armada Wars galaxy and due to the "theatres of war" aspect of the story I need to know exactly where each scene is taking place.

It's much easier to keep planets separate from other types of location (I also have "star systems" and "regions", so it could get confusing very quickly.)

The "places" category is for non-geographical locations only. As you can see in image 3, such places might be ship-board quarters, a gym, or a particular starship compartment. They could even be a house, part of a town... anywhere really. It's very helpful to know exactly where a scene takes place, other than its street address.

You might also notice that the keywords themselves are prefixed with "Place: " or "Planet: ", rather than just being the name of the thing itself.

This is a searching aid: because of the size and complexity of a series, one keyword could easily be referenced inside another keyword. To remove the hassle of having to deal with any such ambiguity in the future, I build the solution into my system ahead of time by differentiating. So if I have to search for scenes which reference the planet Blacktree, I search for "Planet: Blacktree", and scenes tagged with the "event" keyword for the Battle of Blacktree will not be returned in the results.

It takes a little longer to set up, but prevents problems later on.

A Closer Look at Characters

|

| Image 4 |

As with the keywords above, they have a prefix (in this case "Person: ".)

You might also notice that everyone who has a rank or a role has that included in their keyword, as well as their full name.

For example, Rendir Throam is not just called "Throam". His keyword contains the full monty: "Counterpart Captain Rendir Throam".

This makes his keyword more versatile: not only can I check quickly what his rank is*, I can also use the character keywords to search for all scenes where characters of a particular rank or role are mentioned.

Your method may vary depending on your needs, but I find it useful to tag scenes not only with the characters who appear in the scene, but also any characters who are mentioned.

It is, of course, entirely possible to have a separate "Mentions: " keyword category for that purpose, although depending on the nature of your text that might not save much time.

* Side note: Rendir Throam is referred to as a 'captain' because that is his rank in the hierarchy of the Imperial MAGA. It is not equivalent to the naval rank of starship captain.

Keywords on a Scene

|

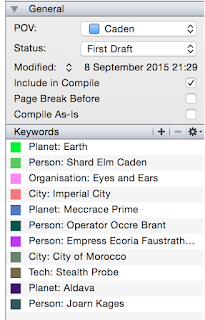

| Image 5 |

Image 5 shows what keywords will look like when they are added to a scene.

By clicking on the + symbol on the keywords pane, you can create a new keyword just on that scene. It will however then be added to the keywords list as an orphan (i.e. with no parent category), so I recommend that you instead add your keywords through the project keywords panel.

To bring up the panel, just right-click in the keywords list, or click on the cog, and choose the option to 'manage project keywords'.

You can drag new keywords into a parent category, and also drag them onto the keywords list for the current scene.

You can drag new keywords into a parent category, and also drag them onto the keywords list for the current scene.

Colours are added automatically by Scrivener, but if you are very specific about what you want you can always allocate colours by keyword category.

You can see in image 5 that this scene is a first draft, and it's from Elm Caden's point of view. This scene is taking place on Earth. While there are two other planets referenced in the scene, and therefore it has three planet keywords, Earth is also the value set in the "planet" field for this scene's custom meta-data. This means that I can use a keyword search to find all scenes which refer to Earth, and a meta-data search to find all scenes which actually take place on Earth.

We can see by looking at the other keywords for this scene that certain people appear or are mentioned, as well as organisations and technologies. If we were trying to ensure consistent behaviour for characters, or track possession of an object throughout the story, searching for the relevant keywords makes that task really easy.

Leveraging Keywords

|

| Image 6 |

Use it.

The search box is versatile and valuable. It can search in various different places (document titles, text, notes, synopses, keywords, custom meta-data, POV tags...), and saves you a lot of time if you use it well.

Search results get sent to a pane which overlays the Binder.

|

| Image 7 |

There are a couple of important things to note here:

1: The results come from all documents, not just those in the compile group. Hence here we see documents from both The Ravening Deep and Steal from the Devil (scenes from List of the Dead do not appear because I've not yet gone through it to tag them all.)

2: Scrivener appears to search down through the hierarchy of documents. So here, we see the scenes in the order in which they occur in the project, but because of how the Binder is arranged (see image 1) the books are out of sequence.

When you have a set of results like this, there are various things you can do with it. You can save the list as a Collection, which can be used in all manner of ways. One particularly funky way is to export it to DropBox, from which it can then be imported as a set of editable flash cards by DenVog's Index Card app.

Index/flash cards are a great way of playing around with scenes, changing up the order and figuring out whether or not the approach you are taking is the best one. Since the Index Card app allows editing, you can mess with the contents even when you are away from your computer, and re-import the scenes to Scrivener later on.

Final Thoughts

Keywords are flexible and powerful. They can be used to keep track of people, places, things, and events, as I have described above. But they can also be used to assist the writing process. For example you might use keywords like this:

- "Single-scene chapters".

- "Very short scenes".

- "Points of conflict".

- "Double meanings".

- "Changes of heart".

There really is no end to the ways in which you can leverage this powerful feature of Scrivener to assist the planning, writing, proofing, and editing processes.

Scrivener is free to try for 30 non-consecutive days, and is available for Mac and PC.

The trial will only count days during which the app is actually open.

Get it here: Literature and Latte - Scrivener Writing Software.

Great article! Thanks so much for sharing your expertise. I never paid much attention to keywords before but I can sure see the advantage of them now.

ReplyDeleteYou're welcome, and thanks for the feedback!

DeleteI suspect our little keyword friends are greatly overlooked throughout the author population, probably because we are so used to using dog-eared paper copies full of post-it notes.

I think the Universe must like my current series because it pointed me to your wonderful article exactly when I needed it most. Genuine thanks for this little masterpiece of absolute clarity - you should have been a teacher.

ReplyDeleteGlad it helps! Thanks for the feedback.

Deletethank you for taking your time to share this information. I have been trying to figure this out for awhile--very helpful. Goodday to you, Sir.

ReplyDeleteYou're welcome! Glad it helped and I appreciate the feedback.

Delete